Интервю с Дмитрий Глуховски

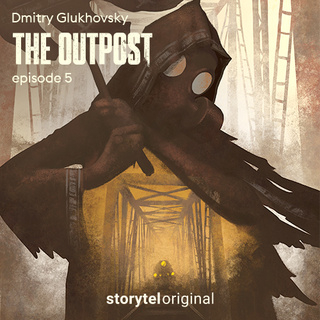

On May 27th, one of the biggest names on Russia's SFF scene, Dmitry Glukhovsky met more than 200 of his Bulgarian fans in a special event in the underground of the National Palace of Culture in Sofia, drafted by his publishers of Storytel Bulgaria and matching the style of his newest work, the audio series Outpost. The Bulgarian premiere event comes only days after the worldwide premiere in Moscow and the novel has been created directly for Storytel's audiobook platform which has been present for a while on the Bulgarian scene as well, offering more than 500 titles in Bulgarian and a thousand times more in English and other languages. Some of them naturally being science fiction and fantasy. The time has come finally to present you with our exclusive interview with Mr Glukhovsky, courtesy of the organizers, to let you remember fondly the nice events from the end of May and hopefully to rekindle your interest for this new work and his former novels, which are definitely worth your read if you haven't stumbled upon them yet.

On May 27th, one of the biggest names on Russia's SFF scene, Dmitry Glukhovsky met more than 200 of his Bulgarian fans in a special event in the underground of the National Palace of Culture in Sofia, drafted by his publishers of Storytel Bulgaria and matching the style of his newest work, the audio series Outpost. The Bulgarian premiere event comes only days after the worldwide premiere in Moscow and the novel has been created directly for Storytel's audiobook platform which has been present for a while on the Bulgarian scene as well, offering more than 500 titles in Bulgarian and a thousand times more in English and other languages. Some of them naturally being science fiction and fantasy. The time has come finally to present you with our exclusive interview with Mr Glukhovsky, courtesy of the organizers, to let you remember fondly the nice events from the end of May and hopefully to rekindle your interest for this new work and his former novels, which are definitely worth your read if you haven't stumbled upon them yet.

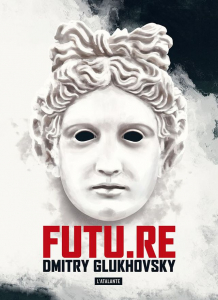

Dmitry Glukhovsky himself rose to fame with Metro 2033 as very young. The novel has been first published on internet forums, asking for fellow readers' feedback but its popularity has rocketed until it was officially published some years later. The Metro trilogy concludes with Metro 2035, a sort of reinterpretation of the events from the first book and although it has been his most successful series up to date, his other works, among which Futu.re, Dusk, Stories of the Fatherland and his new novel Text, merit your immediate attention as well. He has been a journalist in locations such as the Baikonur and the North Pole and he has gathered some following as a critic of Mr. Putin's presidency. He likes to experiment with many formats, he's had an active part in the develpoment of the Metro games which complete the cannon of his series and he also runs amazing websites for his books, full of video, illustrations and other art.

His newest experiment, the audio series Outpost takes us to some time after a deadly civil war has transpired that has seen the use of weapons for mass destruction. Russia is just a remnant of what it has once been. The border of the Muscovite empire runs just a couple hundred miles from the city, on the shore of the river Volga that has been completely poisoned with radioactive waste. Nobody has crossed the bridge to the other side for years...

The Morning

I meet Dmitry and Annie from Storytel Bulgaria in his hotel apartment somewhere around the National Palace of Culture which later that dat would be the stage for the grand premiera of the new series. Phonecalls and morning chaos reign. Mr Glukhovsky is a bit tired from his travels but owing to the organizers' generous praise, he greets me warmly and he's obviously happy to let me pick his brain and share some thoughts with our local SFF community. Even though he's become famous super early, Dmitry is extremely easy to speak to and cracks lots of jokes all the time. We sit comfortably and dive right in.

SD: Okay, so let's start with the big event. You have a new novel-cum-audioseries, it runs on Storytel's platform and is called Outpost. At the same time, there is also a graphic novel of yours that's called Outpost? Would you share the story around this?

DG: So it's been a project that was in development for quite a long time. At first, it was an idea of a TV series, right? And the TV series handles the issue of a Russia that collapsed and fell apart after a Civil War. And it was just a fraction of what it once used to be. And there was this bridge into nowhere and the outpost that that guarded the rail.  So like a very, very understandable image: George Martin has it with his Wall, you know, it's kind of like the border frontier. The Frontier is a very romantic feeling. Nothing new and groundbreaking. The only question is what's on the other side? The enemy, the other, the likes of you..? The ones who think that they are the good and you the evil, the monsters, you know, or extra-terrestrials. Or nothing. It's this feeling of defending or being on the frontier, on the boundary of unknown, that is incredibly tempting, I think. And then, of course, it's not my shoe, it's all over fantasy and sci-fi. Now, the innovation that I wanted to bring was exactly about the country that collapsed. Reusing the old elements and add this something new, you know.

So like a very, very understandable image: George Martin has it with his Wall, you know, it's kind of like the border frontier. The Frontier is a very romantic feeling. Nothing new and groundbreaking. The only question is what's on the other side? The enemy, the other, the likes of you..? The ones who think that they are the good and you the evil, the monsters, you know, or extra-terrestrials. Or nothing. It's this feeling of defending or being on the frontier, on the boundary of unknown, that is incredibly tempting, I think. And then, of course, it's not my shoe, it's all over fantasy and sci-fi. Now, the innovation that I wanted to bring was exactly about the country that collapsed. Reusing the old elements and add this something new, you know.

So the first idea was over five years ago, maybe even as far as seven years ago, when Russia was still rich and happy and was preparing itself for the Olympic Games, and pretended it's quite nice. There were no mass protests. Back at that time, many were really rich. But there was a feeling that something is wrong. Russia cannot be rich and happy. We have to suffer. What's wrong? Why are we not suffering? It was like in a way people got fed up with material wealth. You know, like, an IT person would graduate from Moscow University and they would immediately like to earn $2,000. If she's not like 20 years old not earning $2,000 she's not working. She's not working. "What, a thousand? No! Another internship, fuck, I did five years of education. I would like my 2000 here". Now, that was the time, you know.

SD: Yeah, that sounds much familiar..

DG: The prices of the flats doubled almost every year. And so did the salaries. It was a time of incredible growth. A lot of people in the middle class appeared. But then a lot of people kind of felt nostalgic for the hardships. And so I formulated this outpost as a country, as Russia, where the hardships are back again. So you take the urban environment that you know, and you repurpose it so the apartment blocks become fortresses. The trucks become roaming fortresses with machine guns. Probably with the flags with the face of Jesus on it, like they did in the old Russian times in the Middle Ages. And then all the migrants becoming the new horde of Temujin (Ghenghis Khan -- editors note), becoming the new Mongols.

It was kind of fun. We were making fun. And so they said, let's write it. So I wrote it. And then we even shot the pilot of the show. And then it started coming true. Not in Russia, but in the Ukraine, with Russian help. Then, after the street protests of 2012 in Russia and then the successful protests of Maidan, Putin decided to take initiative, grabbed Crimea and send Russian volunteers into Donbass. And whatever was science fiction and dark fantasy, became reality. So the apartment blocks did become fortresses. And the trucks did become, you know, there's this new Dan tanks, and they were wearing the flags with Jesus faces. It was so crazy, but all came true. But also, because of the seizure of Crimea, it became illegal to speak about collapsing, about Russia falling apart because if you doubted the integrity of the country, it became political.

SD: You mean actually illegal?

DG: Oh, yeah, there was an article in the Criminal Code saying it's illegal to speak about Russia losing its integrity or falling apart. Questioning Russia's integrity became a criminal cause. So all of the sudden TV channels for which we filmed went: "Uh, no". Because this used to be dark fantasy fun. Now, it's reality is politics. So no.

And then I thought that maybe I can repurpose it for the United States. I changed the concept. And I turned that from the falling apart to the influx of migrants. And so the Outpost, the American version is also like an outpost, but it's kind of the coming of the others. So it's a bit different, though the concept is similar. There is the outpost that is in middle of nowhere. And there will be a wave of migrants coming from an invasion, and you let them in and they destroy the house.

SD: Which also became an issue nowadays for the Americans.

DG: Exactly, it was like, this story became an issue two years later. And then over and over again with the refugee crisis in Europe...

SD: So now we know who the prophet in Outpost is based upon..!

DG: Yeah. You know, it's funny, because I'd never thought of myself as a prophet. But a lot of ideas, they just came true very soon, in a couple of years. And if I don't use them, somebody else does. So I decided I should write quickly, before other people exploit them. So when Storytel came to me and proposed to do something together, I said, okay, we're going to do an audio series, since I already got a series in my mind. And I've got a marvelous story for it. And we get to do the same kind of series like what you have on TV, which is basically one hour episodes, cliffhangers, different storylines with different characters, clashing, evolving... whatever you have in a TV series, but just without pictures. So because there is no pictures, the language will be more sophisticated than in screenplays, when it's very technical. It was going to be a lot more artsy, because I need to stimulate people's imagination. And there's going to be music.. and it's going to work out.

DG: Yeah. You know, it's funny, because I'd never thought of myself as a prophet. But a lot of ideas, they just came true very soon, in a couple of years. And if I don't use them, somebody else does. So I decided I should write quickly, before other people exploit them. So when Storytel came to me and proposed to do something together, I said, okay, we're going to do an audio series, since I already got a series in my mind. And I've got a marvelous story for it. And we get to do the same kind of series like what you have on TV, which is basically one hour episodes, cliffhangers, different storylines with different characters, clashing, evolving... whatever you have in a TV series, but just without pictures. So because there is no pictures, the language will be more sophisticated than in screenplays, when it's very technical. It was going to be a lot more artsy, because I need to stimulate people's imagination. And there's going to be music.. and it's going to work out.

SD: So I listened to a couple of episodes... and I think it works, absolutely. And I think you guessed my next question, which was about what distringuishes an audiobook from an audio series. You mentioned it has to follow the TV show structure. But I was wondering, on Storytel you have all of the episodes together at once, like the Netflix model. Would you rather have them come out like once a month, so that there's more suspense and all that?

DG: Yeah well the way Storytel fulfilled it for now, because they were in a rush, is not exactly what I had in mind. I thought that should be more of a radio play with several actors, and some noises and sounds, and also music. And I would read the author's part, whereas actors would read their own characters. Maybe it will come later. I'm very much stimulating Storytel Russia at least, to do that as a radio play, then whether you would prefer to consume everything at once, or you prefer to delay things to a bit -- it's all about your preferences.

SD: In Russian, you read it, right?

DG: I read it, yeah.

SD: Right. So you speak, like what, a thousand languages? I was wondering have you listened to any of the other translations in languages that you know?

DG: No, not yet. Actually, Bulgarian is the first foreign one. Annie (from Storytel Bulgaria -- editor's note) let me listen to it for about 40 seconds. The the voice is good but other than that, I don't understand much. Maybe like 30%, even though it was me who wrote the text.

SD: I think he (Momchil Stepanov does the Bulgarian voicing -- editor's note) does a great job conveying different characters. But it just so happens that when I was coming back now, during the weekend, I had this sort of sensory experience with some guys, where you close your eyes and for a couple of hours experience everything just with your ears and the other senses. The idea obviously being that the eyes bring a cognitive reaction immediately -- you just conceptualize what you see. Whereas when you hear maybe it's the other way around. So I was wondering if what you're trying to convey with your voice when you're reading, when you compare it to these other actors that are doing the translations, do you think that they succed in bringing up the same feeling about the the atmosphere of Outpost?

DG: Hmm I don't think so. So everyone is interpreting, you know, I'm interpreting too. The thing is, the way I wrote it in Russian, I'm mixing styles, I'm very often using the spoken language, with lots of inversions and not everyone is getting this idea but I'm changing the order of the words to put the more important word first. Sometimes people just take a look, they register it as inversion, or as slang but subconsciously that can actually get you to pretty interesting emotional effects. Now, most foreign languages, since they are not Slavic, this is most often lost. They just retell basically, in their own way, what I wrote. In Slavic languages that allow the same flexibility and sentence construction, it maybe can be done. I don't know how they got it translated into Bulgarian. But anyway, you know, I'm pretty calm about it. I just understand that in any language translation is a retelling.

DG: Hmm I don't think so. So everyone is interpreting, you know, I'm interpreting too. The thing is, the way I wrote it in Russian, I'm mixing styles, I'm very often using the spoken language, with lots of inversions and not everyone is getting this idea but I'm changing the order of the words to put the more important word first. Sometimes people just take a look, they register it as inversion, or as slang but subconsciously that can actually get you to pretty interesting emotional effects. Now, most foreign languages, since they are not Slavic, this is most often lost. They just retell basically, in their own way, what I wrote. In Slavic languages that allow the same flexibility and sentence construction, it maybe can be done. I don't know how they got it translated into Bulgarian. But anyway, you know, I'm pretty calm about it. I just understand that in any language translation is a retelling.

SD: And it always adds up to the text.

DG: Yeah. What's important is, you should be good enough to stimulate a person's imagination. And we're experimenting here, you know, it's not the ultimate masterpiece in the world. It's just a new creative experiment in which we're taking a part.

SD: This is your first time going direct to audio, right? Yeah. So what was most difficult?

DG: Well, you know, I'm pretty trained reading fairy tales to my kids. So I guess I already had a good start. But I was not a big fan of the idea that I should read all the characters. There is this deaf monk character, that he's not hearing what he's saying. There's a girl character, which is a little princess. And there was an old woman character and old man character and former police Colonel character, so you know, how do you do all these voices? I do my best but I'm not sure that my best is good enough. But they said, let's do this, so I jumped in.

DG: Well, you know, I'm pretty trained reading fairy tales to my kids. So I guess I already had a good start. But I was not a big fan of the idea that I should read all the characters. There is this deaf monk character, that he's not hearing what he's saying. There's a girl character, which is a little princess. And there was an old woman character and old man character and former police Colonel character, so you know, how do you do all these voices? I do my best but I'm not sure that my best is good enough. But they said, let's do this, so I jumped in.

SD: Did you feel that you have to be more clear in what you say, compared to when you're writing because when you're writing, people have to take the time to delve into the text, whereas on audio you don't usually go back, listen again, etc.

DG: Well, a lot of people, especially the youngsters, they listen to audio all the time, even on high speed. They can listen to, you know, War and Peace, on double speed, so you know, they kind of know everything that's going in the book, but it's a very comic interpretation. So yes, that's exactly one of the challenges that that you're facing, while you are creating for audio, you need to understand that people do not have the possibility of immediately going back or looking up, looking down, they don't have the entire picture, the only have moment. So you should not exploit the complicated language thing, because people are getting lost. And then you have to make it extremely grasping. It should be dramatic like... in fact, like a TV series, you know. It should be drama and conflict in every scene. Otherwise, people get bored and get lost. It's the overarching challenge in these times of multi-tasking, multi-window epoch, where you've got checking what's up in Facebook and this and that, and mails piling up, and buzzing he news. A lot of competition for your attention, you know? So basically, you should think about how much content you're constantly competing with. As we read in articles, people who do apps, they have Stanford psychologists specialized in attention span working for them. So it's a pretty fucking tough competition.

SD: It seems to work, though. I was just telling Annie that I usually have a hard time concentrating to audiobooks, but this time it worked, it's grabbing.

DG: Because it was meant to be an audio series, you know, so like, attention, conflict, changing viewpoints, keeping you hooked. That's the difference. When you asked me what's the difference between the audio book and audio series, that's it. You bring dramatic structure over from the TV, you reuse it in audio, in literature, so apparently that can work. Pretty happy to be innovating in this -- seems to be the way to make people speaking about you!

SD: Okay, so here we are in Sofia, first premiere after Moscow. Why did you pick it? You've been to Sofia, as you mentioned, ten years ago, has it changed a lot for you?

DG: I didn't see it much last time. It was a one day trip, the launch of Metro 2033. I remember it was a fabulous party. I gave some interview, then they took me to dinner. I think I saw the Cathedral. So that was my impression for the last time. And this time, I think it's going to be pretty much similar. So Sofia didn't change a lot for me.

SD: But what led you to pick it for the first event of the tour?

DG: I didn't really pick anything, it's more like Storytel had Bulgarian be the first language in which Outpost was translated. And also, I was invited to VarnaLit, the festival, they also nominated me for some prize. I have the Polish ComicCon coming just next, so I wanted to combine them.

SD: Have you hopped on Sofia's metro system though?

DG: No, I don't think so. No.

SD: It's much more bigger now, compared to 2008.

DG: Congratulations! So more people can now survive in it during the apocalypse!

SD: Absolutely! Right, so moving on, something about the topics that you tackle in the books. There's obviously the post-apocalyptic thing going on, which made you famous. And you have mentioned many times that a big thing in Metro was showing how people don't seem to learn from the past a lot. So I was wondering, have you been thinking about a post-apocalypse in the past? For example, after the Roman Empire fell, or after the Mongols invaded the Kievan lands? Does that feel like post-apocalyptic? What is the defining feature?

SD: Absolutely! Right, so moving on, something about the topics that you tackle in the books. There's obviously the post-apocalyptic thing going on, which made you famous. And you have mentioned many times that a big thing in Metro was showing how people don't seem to learn from the past a lot. So I was wondering, have you been thinking about a post-apocalypse in the past? For example, after the Roman Empire fell, or after the Mongols invaded the Kievan lands? Does that feel like post-apocalyptic? What is the defining feature?

DG: Well, you have an event in much more recent history, and that's the collapse of the Soviet Union. That's the first reference. Of course Mongols or the Black Death that they brought to Europe, or the collapse of the Roman Empire... the collapse of every Empire, basically, is a little end of the world, because it's also bringing the collapse of the system of values of the cultural coordinates, of the myth, of the political structure, of the idea of a future. The Soviet Union existed only for  70-something years but it was enough ot have at least one generation that lived their entire lives there, people who were born in the Soviet Union and died in the Soviet Union, not knowing anything else in Soviet Union. People who thought they will see the construction of communism, which was the purpose of its existence, establishment of a fairer, juster, world, not just in the Soviet Union, but globally. And a very specific, I would say, distorted vision of the past, of the demise of the Russian Empire, which was described as Kingdom of Injustice. The Bolsheviks saw themselves as a force of justice. But this is a myth -- and when it all collapses, the Empire collapses, the entire Eastern Bloc collapses first, all the republics go and then Russia itself starts crumbling, what with Chechnia and stuff. And you really live in a feeling of a collapsing world where things fall apart. And nothing seems to be real. As a Russian, as a Soviet Russian, you live in a myth that everybody likes you. You think that you brought liberation to the world, and people are grateful to you, but then you get "No, fuck you", you know? We're not grateful at all, we want to get rid of you. We want to be free. And you're like, but I thought we're brothers. And they're like, yeah not really, you came with tanks... And you're like, what tanks, we never learned about tanks in school, etc, etc.

70-something years but it was enough ot have at least one generation that lived their entire lives there, people who were born in the Soviet Union and died in the Soviet Union, not knowing anything else in Soviet Union. People who thought they will see the construction of communism, which was the purpose of its existence, establishment of a fairer, juster, world, not just in the Soviet Union, but globally. And a very specific, I would say, distorted vision of the past, of the demise of the Russian Empire, which was described as Kingdom of Injustice. The Bolsheviks saw themselves as a force of justice. But this is a myth -- and when it all collapses, the Empire collapses, the entire Eastern Bloc collapses first, all the republics go and then Russia itself starts crumbling, what with Chechnia and stuff. And you really live in a feeling of a collapsing world where things fall apart. And nothing seems to be real. As a Russian, as a Soviet Russian, you live in a myth that everybody likes you. You think that you brought liberation to the world, and people are grateful to you, but then you get "No, fuck you", you know? We're not grateful at all, we want to get rid of you. We want to be free. And you're like, but I thought we're brothers. And they're like, yeah not really, you came with tanks... And you're like, what tanks, we never learned about tanks in school, etc, etc.

SD: So for you the defining feature is where the social narrative falls apart. But it's not necessary for a post-apocalypse to have a sharp drop of technology or loss of communication, etc?

DG: Well, people love post-apocalypse I think because the world is getting too complicated. Then when they get to basics, start from scratch. Post-apocalypse, in the modern versions, it's just back to car and gun, you know, and that's it. So people don't want to go before that. They want to go back to the cars and guns. And that's basically that's the world of the 80's. Basically, World War Z. Or The Walking Dead. It's Trump's America. It's it's America before the Internet, you know, that's it. That's all the difference. And when it was legal to kill people, because people are evil. That's it, you know?

SD: The frontier stories.

DG: Exactly. So even if Trump got to power by manipulating social media, the America that he's pitching and promoting is the America before the internet and before the global economy, before it's got too complicated. People are lost in this modern world's complexity. And so that's hence the popularity of the post-ap, and then the rehabilitation of the primeval thing, you know.

SD: Right. So there's another image that I want to draw forward, it's maybe not so obvious in your books, but I think it taps into it. You have mentioned the Strugatsky brothers as in influence before. And obviously, one of the most famous things about them is Roadside Picnic. There is the Zone as an image of something intangible, something ineffable that defies human comprehension, and that we can never, in any human way, understand the truth of. When I was listening now to Outpost I strongly felt that you evoke similar imagery with the river that's poisened, with the fog that eyesight, but also the inner sight cannot pierce through. So is there a parallel here?

DG: Oh, yeah, sure. I read all the Strugatsky's when I was a kid. So definitely, that's a part of your background. And it's clear that authors borrow from each other. Although when the last surviving Strugatsky was asked what he thought about Metro he had no idea what this is, and sadly then he died so he didn't have a chance to read it.

SD: Yeah, I mean not that much about being inspired from their work, but rather does this entire idea apply to the river Volga in the series, this idea of something that you have to submit to because it's so much more than humanity?

DG: I think it has to do rather with the fact that Yaroslavl, the city, was the big night stop on the train when I was going to meet my grandmother as a kid. Every summer and every winter, and sometimes in the fall, all the holidays I spent there. And so we stopped in the night in Yaroslavl just ahead of the bridge which is two kilometers long, it's a huge bridge over a super  vast river, as vast as the sea. On the way back you go over it in the daytime, so you can see how it really is. But a the night time, it's a long stop, they bring in new carriages, as a kid you look out of the window and it's scary so that's where this is coming from. Not exactly from the Zone. But from the Zone, I guess you can draw a parallel to the romanticism of the setup. Even more than Roadside Picnic, they have a book called Doomed City. The characters go into abandoned urban spaces, abandoned cities inhabited formerly by some other people, with things written in unknown language, with statues dedicated to who knows whom, abandoned apartments where the things are still there, the books and the furnishings, and you can go and explore. This is what inspired me more, actually, than the Picnic. I loved the feeling of exploring the Zone. But it was much more in the spirit of the Stalker games and the Metro games. I wasn't that much involved with the anomaly, the mysticism, these things from the movie. To me, it doesn't mean anything particular and so I go in other directions. It has to stand for something. Every decent fairytale stands for some kind of drama or dilemma or philosophical issue. From Cinderella to the brothers Grimm's nightmares. It's a story about something that you can refer to, and you can tell it as a clue to some life situation. If it's just fantasy, okay, cool, but...

vast river, as vast as the sea. On the way back you go over it in the daytime, so you can see how it really is. But a the night time, it's a long stop, they bring in new carriages, as a kid you look out of the window and it's scary so that's where this is coming from. Not exactly from the Zone. But from the Zone, I guess you can draw a parallel to the romanticism of the setup. Even more than Roadside Picnic, they have a book called Doomed City. The characters go into abandoned urban spaces, abandoned cities inhabited formerly by some other people, with things written in unknown language, with statues dedicated to who knows whom, abandoned apartments where the things are still there, the books and the furnishings, and you can go and explore. This is what inspired me more, actually, than the Picnic. I loved the feeling of exploring the Zone. But it was much more in the spirit of the Stalker games and the Metro games. I wasn't that much involved with the anomaly, the mysticism, these things from the movie. To me, it doesn't mean anything particular and so I go in other directions. It has to stand for something. Every decent fairytale stands for some kind of drama or dilemma or philosophical issue. From Cinderella to the brothers Grimm's nightmares. It's a story about something that you can refer to, and you can tell it as a clue to some life situation. If it's just fantasy, okay, cool, but...

SD: Well, for me, the river had these religious overtones going on, or at least that's how I felt about it. I guess it was exacerbated by the appearance of the priest that you mentioned, coming out dramatically over the bridge from the other side.

DG: Well, you know, religion steps in every time that Enlightenment steps back. Religions give you structure. They structure the world around you. They solve, again, the complexity of the world, they kind of offer you a blueprint for how to piece it up together. To make sense. We're trying to make sense of it. And if that sense is too complicated, we're just shying away. Every time that a secular explanation of the world fails, religion is gladly stepping in. "Hello, let me tell you about Jesus. Jesus loves you. Hey, how about Jesus?". And so forth.

DG: Well, you know, religion steps in every time that Enlightenment steps back. Religions give you structure. They structure the world around you. They solve, again, the complexity of the world, they kind of offer you a blueprint for how to piece it up together. To make sense. We're trying to make sense of it. And if that sense is too complicated, we're just shying away. Every time that a secular explanation of the world fails, religion is gladly stepping in. "Hello, let me tell you about Jesus. Jesus loves you. Hey, how about Jesus?". And so forth.

SD: So you described Russia, maybe not so much now in 2019, but 10 years ago, as a post-apocalypse in a way. And we witness now a real Orthodox revival in Russia. So is that genuine fall back to religion in the lines of this idea, or is it more like nationalism, conservatism, what have you?

DG: Well, you know, every religion is ideology, and ideologies are religion, to start with. Communism was pretty much religion. And Christianity is pretty much an ideology, as much as Islam. Every good ideology is jealous and it requires you to believe this and that, and it's fighting with other religions because they're stepping on the same ground, there's just this slot that is the human heart. And it should be either religion or ideology, so you're basically struggling for a limited slot in human soul, which is called faith.

SD: But now we have Putin, and we have religion, too. So do they compete?

DG: No, but he has no ideology. Putin is a pure pragmatic. He wants to rule forever and manipulate people in order to rule forever. That's it, he doesn't believe in anything. So think of Putin as Lucifer. He doesn't give a damn about what people believe in. Like Lucifer doesn't really give a damn. Of course, this is too big a compliment for him. But the principles are the same. You know, he is a recruiter for special services, he needs to operate with people's witnesses, exploit people's sinfulness, which is basically Lucifer's forte. So...

SD: Okay... this is still on the record! (laughing) So... another thing I wanted to ask you about, going back to the Metro 2033 times, you have mentioned that, at the beginning, you shied away from romance, sex and these topics in the first book. And then as it progressed, you learned how to tackle these, most famously in Future where it's super violent and full-on. Outpost kicks off with a very awkward first scene with Egor trying to woo Michelle. How did that feel going into? Is it another approach to the whole topic?

DG: Well, I think it all starts with a character. And just like in the Game of Thrones, it's fulfilling to follow the character from the beginning, from the basics. And I think this this awkward teenager thing, is what we have all gone through. And then you can add up, bringing the character, and the reader with him, through situations that the reader can still believe and making him transform into something the reader can relate to.

SD: But now 20 years later, can you realistically remember how he feels?

DG: I think so. Yeah. Well, first, love is always with you. And then the awkwardness. It's just a question of honesty of describing how it really was. Not how great it was, how great you were, how great she was, but rather how awkward everything was, you know, how stupid everything was.

SD: It's very emotional when it's awkward. So it stays in our mind.

DG: Yes, exactly. The first time is emotional. First falling in love. The first excitement of it. That's stays with you, you know you and then you see her again... and you're like, hmm okay.. How did I feel that again? I think I remember, I don't know how realistic it feels. Should feel more or less realistic.

SD: Right. I wanted to ask you just a little bit about fandom culture. Upon its publication, Metro 2033 immediately won the Eurocon prize. Are you active in this fandom? Do you communicate with other fans or authors? Do you visit the conventions? You mentioned ComicCon in Poland?

DG: No, not really. I've just been to a science fiction conference once, I think, in Zagreb. I've been to once to Comic Con Russia. It's with a big pleasure that I am meeting the readers. Usually my readers are not the crazy survival guys that you would expect, you know, but nice, cute, student boys and girls that read books and are super intelligent. They don't fight over who's signing first. At all the the book signings I've done, the bookshop salespersons tell me afterwards: "Oh, your audience is so civilized! They don't smash each other", and I say: "Yeah, they're kind of nice people you know, like, the books are finding nice people for readers". So I have great pleasure meeting with them, taking photos and signing, answering questions. And usually I spend at least an hour to answer everybody's questions so people don't come there just for a single photo. Right? They want to talk of course. So anyway, I like these things but what I don't like is those really nerdy, nerdy culture at conventions. I'm kind of easier with that now, but .. not much. And the easier part is about girls cosplaying anime. Okay, this is good. Boys cosplaying Stalker, kind of less good.

SD: Right. And also it seems you're verging away from genre and science fiction in general? Rumour is Outpost is your last post-apocalypse story? Going other directions.

DG: Yeah. Text,which I will be featuring in Varna, it's more of a realistic thing. And the next book that I'm planning, a real novel, it's going to be like ultra realistic thing again, a family drama about the collapse on the family. Nothing to do with the genre. I really want to have this freedom of experimenting. And the story should really come first and the character should come first. Not that I'm giving up forever on science fiction. But really, I don't want people to think about me as a science fiction author. But just an author. Like, who is Neil Gaiman? What kind of author is he? Who is Bulgakov even? Is he a science fiction author, because he has some purely science fiction things. With dinosaurs, doomsday events, even The Master and Margarita is in essence a mystical story, kind of a fantasy story. So I want that level of liberty. But Outpost definitely for me is, I believe -- in literature at least -- the last venture in the lands of the post-apocalypse. And then this story -- it may have a sequel, Storytel is telling me, but there is an ending anyway, and in the ending you can understand that this setup is just a pretext for something else. The real topic of the story, the real theme of the story, is not about post-apocalypse, it's not about the Lost World. It's about something completely different.

DG: Yeah. Text,which I will be featuring in Varna, it's more of a realistic thing. And the next book that I'm planning, a real novel, it's going to be like ultra realistic thing again, a family drama about the collapse on the family. Nothing to do with the genre. I really want to have this freedom of experimenting. And the story should really come first and the character should come first. Not that I'm giving up forever on science fiction. But really, I don't want people to think about me as a science fiction author. But just an author. Like, who is Neil Gaiman? What kind of author is he? Who is Bulgakov even? Is he a science fiction author, because he has some purely science fiction things. With dinosaurs, doomsday events, even The Master and Margarita is in essence a mystical story, kind of a fantasy story. So I want that level of liberty. But Outpost definitely for me is, I believe -- in literature at least -- the last venture in the lands of the post-apocalypse. And then this story -- it may have a sequel, Storytel is telling me, but there is an ending anyway, and in the ending you can understand that this setup is just a pretext for something else. The real topic of the story, the real theme of the story, is not about post-apocalypse, it's not about the Lost World. It's about something completely different.

SD: Is there a point in the future where we're learning from the past doesn't make sense anymore. Where nothing from the past is useful to us as a species. This singularity point, or what have you.

DG: I do believe that humans, biologically are pretty much the same as they were in the Stone Age. You can read about it at Yuval Harari's or even at the Bible, if you will, we have not been changed. So the technology is only helping us better to be what we've always been. We always needed social "likes". Facebook has given us distilled likes, just as McDonald's is giving us sugar and fat and salt that we've looked for, but never found in such amazing concentration. And that's exactly why social  networks are unhealthy. Because they're overdosing us with these likes and emotions. And we're not prepared and we're feeling wasted on that. But back to the point, we're still the same creatures, and we will be up until the moment when we start redacting ourselves, redacting our genes. Then possibly, if this is legal and ethical, will become something different. But no technology other than this will alter us. Virtual Reality, artificial intelligence, bionic prosthetis, whatever, we're still the same monkeys, you know, with the same monkey wishes and monkey fears. And Cambridge Analytica is proving that beautifully, right. You know, we're very progressive, we have Uber and we have artificial intelligence and data, but we fear to lose the job, we fear the immigrants and the gays, everybody alien, so it's the same thing over and over again, like in Hitler's times. So yes, we do not learn anything because every new generation is born tabula rasa, and has to be retold everything and better off is they live through a situation themselves. That teaches them because it's super difficult to learn from the school textbooks that are boring and you cannot relate to them. So I don't think that this singularity point is going to be brought to us by virtual reality, artificial intelligence or something. But when we stop being humans, like in the book Future, where we get rid of the fear of death, for instance, that is going to change us. It's about stopping being human. Ageing and being human is one of the two main themes of my exploration, truth and lies is the other one. So when you're not getting old, a lot of concerns have gone away. Or if you stop being attracted to other people and seek a partner, then this is all different. Not needing the other half. That makes you maybe godlike, less animal, definitely, but definitely less human. All those things will change us and they can turn us into something completely different. That I wouldn't like to be.

networks are unhealthy. Because they're overdosing us with these likes and emotions. And we're not prepared and we're feeling wasted on that. But back to the point, we're still the same creatures, and we will be up until the moment when we start redacting ourselves, redacting our genes. Then possibly, if this is legal and ethical, will become something different. But no technology other than this will alter us. Virtual Reality, artificial intelligence, bionic prosthetis, whatever, we're still the same monkeys, you know, with the same monkey wishes and monkey fears. And Cambridge Analytica is proving that beautifully, right. You know, we're very progressive, we have Uber and we have artificial intelligence and data, but we fear to lose the job, we fear the immigrants and the gays, everybody alien, so it's the same thing over and over again, like in Hitler's times. So yes, we do not learn anything because every new generation is born tabula rasa, and has to be retold everything and better off is they live through a situation themselves. That teaches them because it's super difficult to learn from the school textbooks that are boring and you cannot relate to them. So I don't think that this singularity point is going to be brought to us by virtual reality, artificial intelligence or something. But when we stop being humans, like in the book Future, where we get rid of the fear of death, for instance, that is going to change us. It's about stopping being human. Ageing and being human is one of the two main themes of my exploration, truth and lies is the other one. So when you're not getting old, a lot of concerns have gone away. Or if you stop being attracted to other people and seek a partner, then this is all different. Not needing the other half. That makes you maybe godlike, less animal, definitely, but definitely less human. All those things will change us and they can turn us into something completely different. That I wouldn't like to be.

SD: Okay. My final question is about the game that we made together with Storytel, asking our audience about some questions for you and this is the one we picked. But I want a new answer! So, it's dusk and you're alone in the subway in the Moscow subway, and you have to pick a station, but not one of the familiar ones where you grew up, etc -- a new station where you should start a new adventure. Which one do you pick?

DG: A new adventure, right?

SD: Something that we will inspire you for a story.

DG: Ooookay. I would pick Sevastopolskaya. Why is that you will probably learn in four years or so.

SD: Nice! Well, thank you very much for being with us and here's wishing you a super nice time in Bulgaria. See you tonight!

Tonight

It's a leisurely walk down the last few metres of the ramp that leads to the underground bowels of the National Palace of Culture, now decorated in post-apocalyptic tones by the organizers. The warm afternoon melts into the coming evening that should complete the last strokes of the setup. Green lights, naked concrete, beer everywhere. We sit at the front. After a short introduction by Storytel and Ciela Books, his main publishers, Dmitry takes the mic. At the start he runs over most of what he have already spoken about with the story of the project, sprinkled through with his usual mix of wit, political commentary and Game of Thrones quotes.

A little more attention falls on the cost of creating the Outpost. Apparently the biggest share of it boils down to his own pay for the voice acting so the entire affair is obviously much cheaper than what it would have been as a TV project though of course the audio-only format comes with its own set of difficulties.

A little more attention falls on the cost of creating the Outpost. Apparently the biggest share of it boils down to his own pay for the voice acting so the entire affair is obviously much cheaper than what it would have been as a TV project though of course the audio-only format comes with its own set of difficulties.

In the series format you usually have a very clear and concise structure, these many minutes for setup, this many minutes for payoff. Everything runs on strict rules so that the story's rollercoaster can turn smoothly and bring you to where the author wants you to be at the end. For me, this was a challenge, following so many rules, but it was interesting. When you go out of your comfort zone, do something that you haven't done before, you discover this new emotion that you pass through to your readers. – Dmitry Glukhovsky

I manage to sneak in a new question amidst the journalist frenzy. It's interesting to know how this same censorship that has forbidden him to do the TV series for Outpost has let him publish Stories of the Fatherland, a very politically charged collection of satirical stories. It turns out to be quite the story. Mr Glukhovsky has been formerly invited to write for the Russian Pioneer magazine, an issue that is run by journalists from Putin's circles and targets the mighty and rich from Russia's oligarchy. The publishers seem to like his stuff a lot but eventually the content, rich with autiobiographical over the top stories of high-end politicians about their first bycicle or their first love, proves too much contrast with his own stories about vodka being poisoned with viruses and Gazprom trading with Hell for natural gas. Dmitry had to abandon the project but the stories are later collected in this issue.

Despite his many criticisms for the way that Russia is being governed, you can feel acutely both now and in our conversation earlier during the day his love for his mother country. It seems that his disrespect stems exactly from this origin point, his pride for Russian culture and Russion history, and his critical reading of the sociological processes that have led to a deadlock strangling Russian potential. Glukhovsky tells us about his childhood and his father, translating Serbian poetry, smoking all the time and probably setting off Dmitry on his literary career. Other SF writers and Russian notaries, along with life itself and obviously Mr Putin are cited as major influences in his work. We also hear some interesting thoughts about his writing process that Mr Glukhovsky likens to a tree, always branching, with you having to weave those branches back in. We also learn that each new books brings him a new set of white hairs for this constant struggle to deal with the creative chaos (which he mostly does with meticulous notes) and with his creative mind (which he mostly does with coffee and sugar).

The final questions from the audience are, as expected, about the end of the Metro saga. When does a world run out, when should we put an end to it? Mr Glukhovsky lets us know that even though the literary clothes for the series are firmly put in the wardrobe now, the world will continue to live in Metro's Universe (see below -- editor's note) as well as, of course, in the Metro video games that he consults and that are integral part of his cannon. We also learn a little about his tens of ideas for new works, among which AI plots and alternative Soviet histories.

After the official part is out, the party the Dmitry has been waiting for finally begins. A single image of a really unique Metro cosplaying youth with his gas mask and a skate running down the ramp, bolts to my memory. I think Mr Glukhovsky's theory for the lack of appeal of male cosplay falls apart quickly. I leave the place runinng after an errand to complete the story of Outpost's appearance on the Bulgarian scene.

After the official part is out, the party the Dmitry has been waiting for finally begins. A single image of a really unique Metro cosplaying youth with his gas mask and a skate running down the ramp, bolts to my memory. I think Mr Glukhovsky's theory for the lack of appeal of male cosplay falls apart quickly. I leave the place runinng after an errand to complete the story of Outpost's appearance on the Bulgarian scene.

I catch up with Hristo Blazhev, the guru from Ciela Books who shares with me some details of his time with Dmitry. Hristo turns out to be a fan of these same Stories of the Fatherland and he remembers fondly the gesture that Dmitry's agents have extended to him by not requiring the copyright payment in advance but only after the publication, thus putting their trust in bringing the book over to Bulgarian audience. It has been a successful gambit. Atypical for SFF stories collection, it has sold well. With Glukhovsky that's easy for Ciela but it's rather the exception.  Upon his coming to the publishing house, Mr Blazhev has immediately claimed the process over publishing Glukhovsky and it seems he is most proud with the edition of Futu.re which to him is the author's high point, his magnum opus. Although he acknowledges the literary qualities of Dmitry's new novel Text, he shares sadness over the fact that the author has abandoned the genre. Hristo and I share the love for the fantastic. Curiously, Text hasn't sold so well yet and Mr Blazhev puts his hopes on a competition that Ciela wants to organize for a Bulgarian addition to the Metro extended universe. One of the questions I haven't managed to ask directly to the author has been exactly about this quite unique cannonized set of fan-fiction that paints the picture of Metro's post-apocalyptic future in other locations. Mr Glukhovsky himself has had high praise for the St Pertersburg and the Italian story and apparently now we will officially have a Bulgarian one.

Upon his coming to the publishing house, Mr Blazhev has immediately claimed the process over publishing Glukhovsky and it seems he is most proud with the edition of Futu.re which to him is the author's high point, his magnum opus. Although he acknowledges the literary qualities of Dmitry's new novel Text, he shares sadness over the fact that the author has abandoned the genre. Hristo and I share the love for the fantastic. Curiously, Text hasn't sold so well yet and Mr Blazhev puts his hopes on a competition that Ciela wants to organize for a Bulgarian addition to the Metro extended universe. One of the questions I haven't managed to ask directly to the author has been exactly about this quite unique cannonized set of fan-fiction that paints the picture of Metro's post-apocalyptic future in other locations. Mr Glukhovsky himself has had high praise for the St Pertersburg and the Italian story and apparently now we will officially have a Bulgarian one.

We are planning a competition for our own Metro. We have the paperwork done, we just need some time to pull it off. And seeing how Dmitry will likely not write about this universe again, we definitely plan to collect the works from the extended universe and publish them. – Hristo Blazhev

Our conversation turns back to our favorite sore point -- the seeming inability of SFF translations to be profitable for the Bulgarian pubishers. Yes, Glukhovsky and Lukyanenko have been reissued successfully a couple of times but those are big names with tradition on the market and they are also in Russian, so harder for the Bulgarian public to read as original text. Unfortunately many other contemporary stars such as Peter Watts and Paolo Bacigaluppi haven't done quite so well. It's not an easy task.

I want to appeal to the fans to buy more Bulgarian translations lest they disappear entirely from the market.. – Hristo Blajev

With these final words I leave Hristo. My final conversation for the night is with Vassil Velchev, the Bulgarian translator of Outpost as well as of many well-known Polish and Russian SFF novels, including the infamous Witcher. Vassil and I go way back through conversations, arguments and projects -- I have even taken part of his academical studies on polyglots back in my crazy times trying to learn Thai, Indonesian and Greek at the same time. For Mr Velchev Outpost is apparently the favorite work of Dmitry Glukhovsky, on par with Futu.re. He considers the series to be a more mature and interesting delve into the topics of the distorted, unclear past in the post-apocalyptic epochs that originally drew him to Metro. Does the translation of an audio-series pose any differences compared to books? Not really, says Vassil, but he finds Outpost dynamic "to the extreme", compared to the author's other works, thus echoing Dmitry's own words about the need for the dramatic effect in nigh every scene.

Pragmatically speaking, this was the hardest book for me, purely from a language standpoint. He uses, sometimes way too much, very low-frequency words, difficult to find. I remember one specific example of a word I was not able to find anywhere until I finally got a hit on Google and it turned out that it was in a forum where the German translator of the same book had asked about the same word... – Vassil Velchev

What seems most impressive to him is Mr Glukhovsky's venture into the realm of the psycholingustics which turns out to be Vassil's own area of academic research nowadays. To him, the novel has some really original ideas in this respect and would definitely offer something of worth to anyone interested in how language influences society, even with a fantastical turn in this case. We part ways on the question of his future projects. Unfortunately nothing genre his way as well but he shares insight on a very aggressive biography of Mr Putin that he's translating currently. It seems rad.

For the brief time Storytel Bulgaria has spent on the scene, they seem to have really shaped up a well crafted product and the visit of a name as big as Mr Glukhovsky is a testament to their serious intentions. The platform is sure to extend and maybe it is from here that the speculative genres can finally gain a hold and make a comeback to Bulgarian markets, as it was during our childhoods. We're crossing fingers and waiting patiently and for you guys, we promise a much more detailed investigation on what Storytel has to offer to the fans of the fantastic, as well as obviously a full-fledged review of Outpost. The summer beckons!