Интервю с Питър Уотс

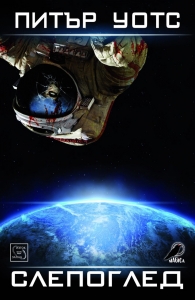

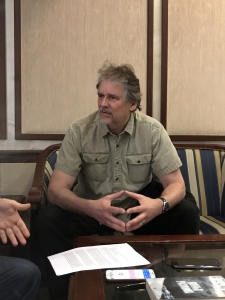

С Питър Уотс, авторът на Слепоглед, Отвъд разлома и още много сериозна научна фантастика, се срещаме на кафе в лобито на хотел Downtown, благодарение на ентусиазираната подкрепа на организаторите на фестивала Ratio, по чиято покана г-н Уотс е в България. В последния момент се сдобиваме с книга за автограф и се впускаме на пълна пара в разговор за съзнанието, аквариумите, трансхуманизма и, разбира се, Дилейни.

Moridin: Hi Peter and thanks for having us! Let us first introduce ourselves, we write for an online science fiction magazine called ShadowDance and obviously we’re great fans of your work. And a part of what we do is a lot of initiatives – with the fandom, with native authors. A lot of our staff are doing professional writing, translating, editing…

Random: We are also teaching science fiction at the University and we have something like a publishing platform where aspiring authors can publish their stories.

Peter Watts: That’s pretty awesome – and better than what we have in Canada.

M: Right and there’s also this book-club that we do, that follows the traditional pattern for book-clubs, we gather each month and discuss. It's the only SF club going on around and when Blindsight was on it (PW: My condolences), we had the chance to gauge that sort of cult following that your book has acquired, actually here, in Bulgaria.

M: Right and there’s also this book-club that we do, that follows the traditional pattern for book-clubs, we gather each month and discuss. It's the only SF club going on around and when Blindsight was on it (PW: My condolences), we had the chance to gauge that sort of cult following that your book has acquired, actually here, in Bulgaria.

PW: Quick question – is genre kind of ghettoized in Bulgaria? You mentioned this being the only genre book club, does that mean mainstream book clubs don’t touch that stuff?

R: Well, as far as there are mainstream book clubs… There isn’t a very strong tradition doing this. But yeah, definitely you see here the same situation as elsewhere with regards to the genre.

PW: That surprises me! I thought that Europe isn’t like that and that ghettoization thing happens primarily in North America. Cause you guys’ve got, you know, you’ve got Lem, you’ve got Jules Verne, all the old guys in Europe that seemed to be successful mainstream literary characters who were respected even though they were genre.

M: That’s the thing though, maybe there used to be a stronger genre and fandom tradition in Bulgaria about 10 or 20 years ago but it somewhat dissipates, maybe it’s the social networks, maybe it’s a generational shift, and now seems a bit of a downturn. But we’re all trying to change that and doing what we can. So, you’re actually here for the Ratio Science Forum – are you excited about what’s going on tomorrow?

PW: I am actually scared shitless. It’s obviously not the first time I’ve given a talk but it’s the first time probably in 20 years that I’m about to talk in front of a non-fiction convention – and I haven’t been a working scientist for nearly that much. Well, I still sort of am a working scientist in some sense but in terms of being a full time working scientist – that ended back in the twentieth century. So I've always been able to cover my ass in the past by saying "Yeah, I'm just addressing a bunch of science fiction fans and I'm talking about science but it's not peer reviewed and it's not rigorous, blah blah blah", right? So these guys invited me and when I start looking at some of the other people that they've had and… You know, they have actual molecular geneticists creating glowing green mice -- they have actual people who are experts in their field. So you look at Ratio’s website and you know they actually use the words “peer reviewed”, you know people will be giving rigorous scientific talks that stand up a peer review and everything. We must have gone back and forth ten times with me saying, "Dude, I'm a science fiction writer"… And I'm still not entirely convinced that this isn't some kind of a cruel trap.

But I gotta admit I'm a little less intimidated now because I’ve talked to everybody who's involved in Ratio. You know, you look at Ratio’s website and it looks like this massive multimillion corporate thing – but it’s actually something that this dude and some of his friends work on in their basements. So I feel a little more confident now but I'm still a little apprehensive about it because strangely enough it's a more scientifically rigorous environment that I've been at for quite some time.

M: Right. Well, we have great faith and we’ve worked with these guys before, so you can be easy they’ve made sure all will be good. How have you been enjoying Sofia so far?

PW: Well, I have been treated to a succession of craft beers and that I think is wonderful. Yesterday we sort of hung out and argued about everything from genetic engineering to police brutality in this wonderful little attic with really low ceilings. And, you know, there is this population of dogs just kind of lying around. I would expect them to be – you know, especially in Trump’s America the dogs are vicious, mean, they travel in packs and they rip your throat. But these cute dogs here just kind of lie there and you feel really sorry for them!

Last night after we left the bar, they took me around to various monuments and stuff and there was this one really weird thing -- it's like some kind of a Star Trek transporter accident, it's got the body parts of about eight different animals and it's holding a big camera or something and apparently it's the tomb of some unknown you know soldier (showing the photo of the monument) – yeah like what the hell is that? It looks like kind of an outtake on John Carpenter's The Thing.

M: (having no idea what the monument is but definitely not a tomb of some unknown soldier) Umm, okay, yeah, that will probably provide inspiration for a story…

PW: Yeah, and I’m told that there are horrible danger zones into which one does not go because they cut you open and steal your organs for trash but I still haven't seen all that, I've only been to the nice parts.

M: Funny thing you mentioned beers and restaurants – last night we were in this Italian restaurant and the waitress whom we’ve met before said to us, "Hey I know from Facebook that you guys do this magazine, right, do you know that Peter Watt’s coming tomorrow?" And we said, yeah, we’re even taking an interview, and she’s like – "Oh, my boyfriend is a great fan and he’s always had some questions" and it turns out he’s a marine biologist. And so, we were like – well, what are the odds? So we figured we could start with his question which was actually, growing up did you imagine you would become a marine biologist or how did that happen?

PW: Yeah, I remember the exact moment I decided becoming a biologist. I was like six or seven years old, and I was walking home from kindergarten with my friend and he asked me if I wanted to go down and see his aquarium. Now, all I knew about aquariums was that an aquarium was this big building.

I grew up in Calgary which is in the prairie, thousands of kilometers from the ocean. And there was this brewery that made I guess you might call it craft beer (but this was back in the 1960s) and this brewery for some reason had built this cultural icon – it was like a public aquarium on the first floor and the second floor was like this museum of Indians torturing themselves… When I think about it now, looking back, it's probably incredibly culturally insensitive and racist – it showed Indians dancing around a pole and ripping you know, with hooks up through their nipples in a some kind of initiation rite. What did I know, I was like six or seven years old but I didn't even care about that stuff because down on the first floor there was this aquarium. It was this dark green grotto and there was an octopus and there were these fish and sharks. Well, probably nothing so special by today's standards but to a little kid... So to me an aquarium was this building that was dark and green and wonderful and full of mysterious creatures.

And so this buddy of mine says: “Do you want to come down and see my aquarium?”. My immediate reaction is, “Holy shit he's got something like that in his basement?”. So yeah, he took me down to his aquarium and it was like this twenty gallon tank. And I should have been incredibly disappointed but instead I kind of scaled up and I thought: “Wow, anyone can have an aquarium!” And so, you know, I could now complain to my parents until I got an aquarium for Christmas and from that point on it was decided.

M: So, how did your work with marine mammals morph into your writing career?

R: Or let’s focus it a bit, did that influence your view on consciousness, which you explore?

PW: Oh God, no, the whole consciousness came on a lot later, I didn't think about it any more than most people do. Basically from the age of seven I wanted be a marine biologist. At the age of thirteen or fourteen I read a book by a Canadian author named Farley Mowat called "A whale for the killing" and in terms of biology it was in many ways a bullshit book. It was basically his first person tale of how this fin whale had gotten trapped in the cold in Newfoundland and how the asshole local Newfoundlanders had just used it for target practice and run it over with motor boats and basically been horrible to it until it died. But there's been a lot of interstitial stuff in the book about the intelligence of whales. Knowing what I do now about marine mammals – this was all bullshit, it was just some guy who was writing a book. But at the time it was like, "Holy shit, we are such assholes to other creatures, to these others sapient things!" (although I did not know the word "sapient" back then).

And so at that point I sort of focused my marine biology to marine mammals because they seemed to need a lot of help and they seemed to be in trouble. There was this “save the whales” thing and the whaling nations were still – and actually they are still at it. But they tend to sort of go after the minkeys and things that are less endangered -- nobody's taking up white whales or humpbacks anymore except inadvertently through sonar testing and so on which has probably killed them off just as fast… So anyway, that's my history and that's how I focused on marine mammals.

M: Thanks, that’s quite the story! Moving on to Blindsight, obviously it's a book about the mind and what it means in many ways. Both of us are very much interested in the AI field, Random in partcular works that. You are certainly aware of how deep learning is all the rage nowadays and people are talking about it a lot. Thus maybe businesses making use of AI solutions for their own thing can prove a way to fund research into the mind from general. But deep learning is kind of like a black box thing...

M: Thanks, that’s quite the story! Moving on to Blindsight, obviously it's a book about the mind and what it means in many ways. Both of us are very much interested in the AI field, Random in partcular works that. You are certainly aware of how deep learning is all the rage nowadays and people are talking about it a lot. Thus maybe businesses making use of AI solutions for their own thing can prove a way to fund research into the mind from general. But deep learning is kind of like a black box thing...

R: It's very difficult to really analyze what's happening inside, it produces these really great results but we don’t know much about how they come about.

M: And maybe this is what we're going to end up with when it concerns the mind and the brain – do you think there's going to be a limit of what we can understand about how the brain works or are you optimistic we are going to nail it down.

R: And even more complex, not just the physical brain, but the mind...?

PW: I have no doubt that we will, probably sooner rather than later, map the brain down to the molecules. They're actually working on projects to do that. IBM and the Swiss doing that whole big brain project called The Synapse Project where they're basically saying: “Well we don't really know how the brain works but it doesn't matter because if we can recreate a brain in hardware or in software in sufficient detail it will pretty much work like the brain does anyway". Now that may or may not be true but in any case I don't think it will get us any closer to solving the hard problem.

Maybe it'll wake up maybe it doesn't – and if it doesn't that will be interesting because it suggests that duplicating and replicating the information flow through the brain is not sufficient to produce self-awareness. If it does, we still won't know how it works, we'll have just blindly mapped it over here and got the same result but we still don't know why that works. I've got slide that I will give in my talk tomorrow where I basically have a piece of me hooked to two jumper cables -- and that's basically what consciousness is, right? It’s like you’re trickling electricity through meat and the meat wakes up somehow and nobody has the slightest clue how that could happen. So I don't know if the way we approach physics now will every give us that answer.

There is a guy called Thomas Metsinger. He at least made me realize why we might never figure out consciousness. Because consciousness is, the way he describes it, it’s the outer layer looking into the system. And because it's the outer layer looking at the system it's kind of a global variable looking at a bunch of local variables. There's nothing looking at it. So the conscious experience subjectively is always transparent – you’re experiencing it but you can never really examine it from the outside.

And if you imagine a system in which you say, OK let's add an extra layer. Then that layer becomes the global variable and the thing that it’s looking at collapses and becomes part of the local system. So you've got this sort of onion skin all the way down. No matter how many layers you try and stick outside to look in at consciousness, you will never get a consciousness because consciousness is always by definition the outermost layer and there's nothing looking in at it. And, I mean the dude’s a philosopher and I'm not so I don't know… It's one of the very few things about brain science that sort of makes intuitive sense to me when he explains it. And it’s kind of a grim outlook for whether we'll ever understand ourselves because you can never make a box big enough to hold itself. But at least it would give me an excuse for not understanding things. That’s as far as I feel qualified to talk about that subject.

M: But even if AI doesn't “wake up”, as you framed it, it’s still interesting how we interact with it. There was this article by a popular Bulgarian blogger, a couple of days ago, he was creating this kind of dystopian scenario where we delegate government to AI. And those AI are not conscious, they are just sophisticated algorithms that the populace in general doesn't understand and a question of trust arises. So we don't think the AI are conscious or that they're going to take over us but we still don't trust them in a way. So is that an important thing to maybe start addressing already?

PW: You know, I think it's kind of a non-starter. You run into the same objections when you talk about soft driving cars. People say “yes but you know, how do you know that nothing will go wrong?” Of course something's probably gonna go wrong – it has already gone wrong and self-driving cars have been involved in accidents. But the question is not whether or not you completely understand what they're doing – I don't understand what you are doing when you get behind the wheel of a car! The question is not whether or not it will be completely accident free and 100% reliable. The question is whether self-driving cars will kick the asses of human beings in car driving! And they’re gonna be way better than people. So if you've got an AI that you don't understand… Well to this day nobody understands a lot of our politically elected leaders anyway, right? If you've got an AI running the country, at least you know it can't be bribed…

M: That’s probably the big reason for installing it there in the first place, yeah.

PW: Yeah, I mean, I think that because we are afraid of giving up control or giving up the illusion of control, we tend to hold the things that might replace us to a far higher standard than we would hold ourselves. So I think that's a bullshit argument, I think the question is whether they’ll perform better than us and if they perform better than us then by all means bring them on.

M: Right. But probably communication with them in any meaningful way is a problem for the people. Because they may be smart but not conscious, kind of like the scramblers from Blindsight... Is that actually a useful metaphor, to compare the aliens who would behave like that with artificial intelligence?

PW: One thing that I'm focusing on in my talk, and in Blindsight, and that seems to be all over the place is really what difference does consciousness make? The body seems to be able to do a whole shitload of things without conscious involvement. For example, the solution to my master's degree came to me literally in a dream. Like, I was spinning my wheels on these results from three months, I wasn't getting anywhere, I had a dream, I woke up… The mainframe computer wasn't open until 8 AM so I went down to my little V20 computer from Commodore (it had like 5K of memory or something), and I wrote a quick linear regression program just because I didn't want to wait until eight in the morning. This was two in the morning so I spent a couple of hours writing regression program. I ran the results through it, I got incredibly good results which made perfect sense and that was the solution. And I'm not the only on! Science is full of cases where people intuit. Ramanujan, the Indian mathematician swore that the theorems were brought to him by members of the Hindu pantheon, in dreams. Kekule dreamed of the structure of the benzene molecule, right, and this stuff happens all the time. There is increasing evidence that thinking about something consciously actually impairs your ability to make an intelligent decision.

So what does consciousness do other than get in the way?

R: In Blindsight this is clearly one of the central ideas, that consciousness is just a quirk that just happened but isn't really that useful and it's actually wasteful. But I’m guessing you’ve probably have thought in detail about possible arguments in favor of consciousness. So do you have a favorite argument, even if you don't really believe in it, what would be the evolutional meaning of consciousness?

PW: No. You know, there is one fundamental rule of biology that people tend not to grasp when they're not in the field because of the popularization of terms like “survival of the fittest” and evolution is portrayed as this sort of onward optimization. Evolution does not necessarily optimize anything, evolution doesn't even select for anything if there's enough to go around. It's only in the case where you are in the environment that is limited and all of a sudden there are more of you out there than can possibly survive. At that point the fact that some of you are better at grabbing some types of resources than others, that certainly kicks in and that's what shapes the lineage. But really all that matters is that you're better than the competition. And once you're better than the competition there's not a whole lot of selection to further optimize.

So you don't necessarily have to justify the existence of artifacts of biology by finding a purpose for it. People who do that are referred to in the field as adaptationists. Back in the days when I was going through my university education, 99% of all mutations were considered to be harmful. But it turns out now that the vast majority of mutations don't make any difference one way or the other. There's so much redundancy built into the genetic code, there's so many different ways of coding for alanine or whatever, that if you have a single point mutation it doesn't really make that much of a difference. It doesn't express. There's a lot of gene duplication going on so that evolution can play around with all sorts of critical genes but as long as one copy of a gene remains functional, you're not interfering with any metabolic processes.

So it's a really messy system and you don't have to come up with an argument in favor of a lot of these things. A lot of them can just happen. And there isn't a selective pressure to weed it out just yet. That's why in Blindsight I had to come up with something else, with some external pressure.

One of the ideas I'm playing around with, and that might be a future book in the series – is that consciousness may not be useful now but perhaps it can be turn into something that's useful. Maybe it's slow and it's inefficient and it impairs the basic functioning of the brain and the computation but maybe the one thing it has is the ability to edit the layers underneath it. So it has essentially command permissions. And if that can be harnessed in a particular way… I mean really all we use consciousness for now is to justify our gut feelings anyway. We want the oil so we decide we're going to spread democracy and liberate Iraq. We tend to use the conscious self not to control our instincts but to make everything more convoluted and complex. And so rationalize behaving pretty much the same way sticklebacks and spiders and deer all behave, right?

One of the ideas I'm playing around with, and that might be a future book in the series – is that consciousness may not be useful now but perhaps it can be turn into something that's useful. Maybe it's slow and it's inefficient and it impairs the basic functioning of the brain and the computation but maybe the one thing it has is the ability to edit the layers underneath it. So it has essentially command permissions. And if that can be harnessed in a particular way… I mean really all we use consciousness for now is to justify our gut feelings anyway. We want the oil so we decide we're going to spread democracy and liberate Iraq. We tend to use the conscious self not to control our instincts but to make everything more convoluted and complex. And so rationalize behaving pretty much the same way sticklebacks and spiders and deer all behave, right?

So maybe if we could harness that in a meaningful way… An example I have is that the reason we are sort of fucked up as a species now is because to us inconvenience in the short term is more real than catastrophe in ten years. Our perception of time is a relatively recent evolutionary development and so there's this kind of exponential decay. There’s now which is what is really important, and then the further away you get from now in either direction, the less real things seem. So if somebody says, yeah we've got to head off this global warming or we're really in the shit in ten years, but part of taking proper measures means you lose your job… I mean, “Look there's something in ten years, but I want to keep my job”.

So the problem is, if you want to get to where you need to go here but you have to run barefoot over a fire in order to get there most people won't do it because the fire hurts. So suppose we can wire our consciousness to the point where it became more goal-directed, where running across the flames was actually pleasurable, where in fact that action felt good to make those sacrifices on a gut level. Well, you'd have to tweak it because if just running across the flames felt really good and then people would stop in the middle of the flames and burn their feet. So you'd have to have some kind of a conditional loop whereby you have to keep moving forward and if you stop then it hurts again.

So I was thinking maybe we could reprogram consciousness to the point where it actually makes us want to do things that would normally be painful and we would not want to do, in the service of some far off goal. That might be some way of reconfiguring the human brain for a long term perspective.

M: Mind-hacking! It happens to an extent in Blindsight, right? So, going back to the book, apart from the whole mind thing, communication is also a great theme going through it. On one part communication between species that is almost non-existent or I don't know, depends on how you define communication; but also the protagonist is a sort of communicator in between human populations.

PW: Yeah, he's basically the Neil deGrasse Tyson, right, he takes really complex things and dumbs them down so that we can all understand.

M: So, in terms of communication between us, humans… We pretend can reason with each other and understand each other but there's so much going on between any single two individuals that is missing. So do you think that with technology, going forward we will or can tackle this, can we come up with some sort of empathy enhancers or telepathic connection? Or is that even desirable? Maybe we're so used to miscommunication that we are wired for it?

PW: I have absolutely no doubt that it's feasible in terms of developing the technology. The question is selling it politically. The moment you start saying, OK we're going to change our fundamental brain stem wiring, you're going to have people up in arms claiming you're changing the human soul! You know, we were cobbled together by this blind evolutionary processes but that's OK, right. But if somebody actually directs or optimizes then all of a sudden that's not OK. In either case you don’t have any control on your wiring right. The fact that someone comes in and plays around with your brain stem wiring is no more invasive than the fact that evolution played around with your brain stem wiring millions of years before you were even born. But people do not see things that way.

M: There’re probably going to be fractions, right? Enthusiasts, naysayers…

PW: Possibly, yeah. There’s also this thing that there's a reason that most people don't commit suicide. We have a really hard wired desire to protect the self. And the obvious reason for that is, you know, a few million years ago those of us who didn’t particularly care about protecting themselves got eaten or fell off a cliff or whatever and so you got. I mean that’s the one thing that natural selection is really good at doing -- promoting selfishness.

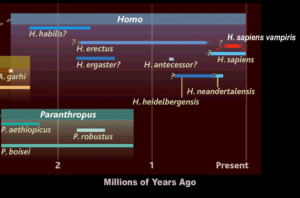

So... The question with this really simple and ancient but circuit is how does it parse the kind of transhumanist stuff you're talking about. Now how does it parse changing? If you come up to your typical transhumanist and say “Hey, you know, you're going to end up  being a super studly guy, you'll be an and immortal android body, you'll be able to leave bodies or leap buildings in a single bound and you'll be able to that have this incredible computational power and you will be able to have sex as long as you like for as much as you like, with as many people as you like all simultaneusly... in the cloud. Take any stupid nerd fantasy and stick "in the cloud" in the end of it and suddenly it becomes plausible. And most people will say “Yeah, that's that's great, yeah, I'm up for that”, because they're not really talking about changing themselves into something else. What they're talking about is optimizing themselves as they already are. They're talking about putting the body essentially to big tupperware container with a longer warranty. But if you actually say to them “You know, we've kind of figured out the the optimal form if you want actually to have higher intelligence (and you want to have) and what that means is we're going to have to turn you into a ten foot long banana slug with a rim of like two hundred blue scallop eyes around your mantle, most people would go “Goddamn it, Martha, that’s just not natural!” Because the whole focal point of being post-human is you're not human anymore. And so what you've got to do is, is you've got this brain stem that wants to protect the self and can it tell the difference between dying versus turning into something completely different? What is the fundamental difference of that? How is that not suicide? How is that not breaking down the cells of your body and just putting it back together in a different shape? Is it still you? And I think that there's going to be an intense resistance to that that kind of thing and it's not rational, it's just built into us, it’s built into the firmware.

being a super studly guy, you'll be an and immortal android body, you'll be able to leave bodies or leap buildings in a single bound and you'll be able to that have this incredible computational power and you will be able to have sex as long as you like for as much as you like, with as many people as you like all simultaneusly... in the cloud. Take any stupid nerd fantasy and stick "in the cloud" in the end of it and suddenly it becomes plausible. And most people will say “Yeah, that's that's great, yeah, I'm up for that”, because they're not really talking about changing themselves into something else. What they're talking about is optimizing themselves as they already are. They're talking about putting the body essentially to big tupperware container with a longer warranty. But if you actually say to them “You know, we've kind of figured out the the optimal form if you want actually to have higher intelligence (and you want to have) and what that means is we're going to have to turn you into a ten foot long banana slug with a rim of like two hundred blue scallop eyes around your mantle, most people would go “Goddamn it, Martha, that’s just not natural!” Because the whole focal point of being post-human is you're not human anymore. And so what you've got to do is, is you've got this brain stem that wants to protect the self and can it tell the difference between dying versus turning into something completely different? What is the fundamental difference of that? How is that not suicide? How is that not breaking down the cells of your body and just putting it back together in a different shape? Is it still you? And I think that there's going to be an intense resistance to that that kind of thing and it's not rational, it's just built into us, it’s built into the firmware.

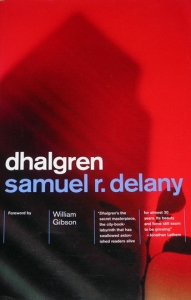

R: So a quick follow-up question on the same topic but from a slightly different angle. A lot of people in the magazine that we work in are great fans of Samuel Delany and on reddit we have read that you are a fan as well. And this sort of translating that Siri does reminds me vaguely of the theory of modular calculus which he explores in Trouble in Triton and The Neveryon Cycle.

PW: I haven’t read The Neveryon Cycle.

R: OK, so very quickly, it's this idea from semiotics: can we actually take any model and translate it meaningfully into any other into any other? Is that possible? That's a question he explores in great detail and I don't think he actually believes it's possible, but he nevertheless explores it. So do you have any thoughts on that, is there some philosophical limit?

PW: I come from the exact opposite side of the campus. I didn't even know what semiotics was until about a year ago and I'm still not really sure that I know. Dhalgren is one of my favorite books, even though it makes no sense, but it doesn't have to, it's like this totally immersive experience that obviously makes some kind of sense to him. I wouldn't be able to make sense in that environment, so why should the reader? But I've read a piece by Karl Schroeder, who you may know, he's another Canadian SF writer who describes Dhalgren essentially as a tale of a semiotic crisis in which subjects and objects become disconnected from each other. And because I don't know anything about semiotics really, I can't comment on it but there was something that felt right about that -- a lot of the stuff that was going on in Dhalgren obviously had to do with flawed perceptions and the flawed connections between ideas of objects. So to not answer your question, because I can't, I’ve heard questions kind of like that before and I've heard them answered by people who know way more about those sorts of things than I do. And I respect those people. But I myself am not competent to comment on them because I don't know what I'm talking about.

R: But what you said about Dhalgren makes so much sense and I think you will win at least a couple of fans more.

PW: You know, I could have sworn that Bowie did Diamond Dogs after reading Dhalgren, but apparently it came out just the year before, so the timing doesn't that fit.

M: Maybe a bit about SF and society and the political role of SF?

R: It's a cliche that science fiction is very good at promoting progressive ideas.

PW: Also extremely reactionary conservative ideas. Let us know they have Robert Heinlein.

R: Definitely. It’s cliche, but do you think that potential is really there and, if yes, where does it lie? Is it the tendency to excite people about science or maybe challenge the social order and paradigms or, even more generally speaking, problematize the issue of what's the Other and what does it take to become the Other?

PW: We're all aware of all these little stories -- you talk to anybody at NASA and it turns out they were inspired by Star Trek, or the first cell flip phones were inspired by Star Trek. First interracial kiss -- on Star Trek! And then it's like “Oh, look, this Reagan's S.D.I. program, you know that was invented by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle…”

M: But it’s not just technology, is it? SF imagines societies as well?

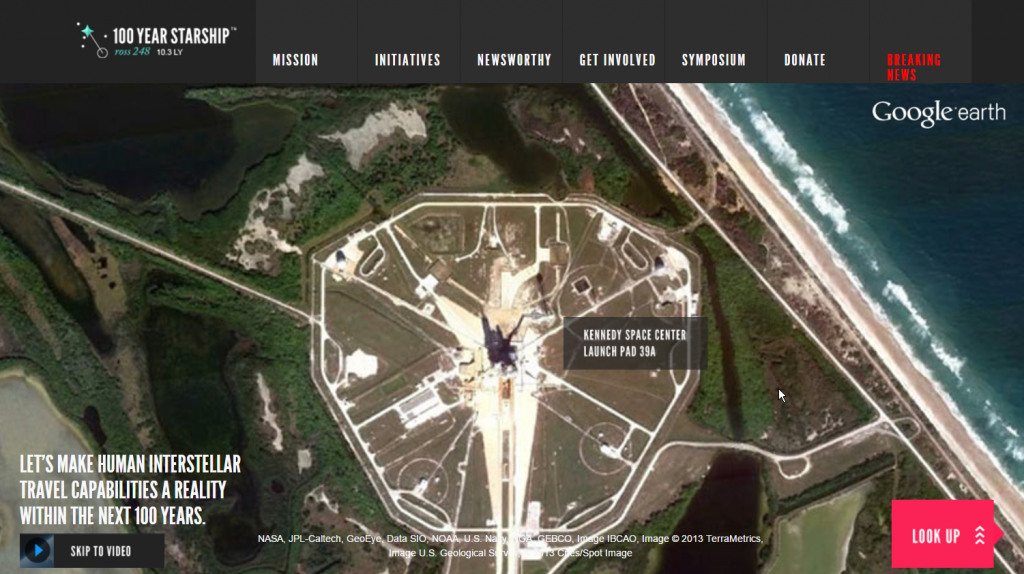

PW: Yeah, yeah, William Gibson predicted cyberspace, invented the word cyberspace. I hear all this stuff and now it's to the point where there are these degrees you can get in future prototyping, right? Companies will hire people who write science fiction to come up with future scenarios that can inform military decisions. And also there's the One Hundred Years Starship Project, where scientists and science fiction writers get together. I've just recently been drafted into the science fiction committee on the X-PRIZE project. So now I’m supposed to help come up with new X-PRIZE goals or something... And quite honestly, I think it's all bullshit. I have read and seen the results of some of these workshops, but they're basically marketing. You might as well get a fucking degree in basket weaving, as far as I’m concerned. I mean science fiction has always done that. Same thing, if you got a degree in future prototyping, it's sticking old wine in new bottles with a fancy label.

In terms of the actual impact that science fiction has, what I actually see is people taking political agendas they already have and cherry picking science fiction to justify that. You know: "Oh yeah, space exploration is really cool and look at all the people who were inspired by Star Trek"; or: "Space-based defense is really cool, look at Larry Niven and Jerry Pournell". What you don't see, is people saying “Yeah we've got to control our population, we've got to cut back on pollution, what about… let's take inspiration from the works of John Brunner.” If science fiction really did have an ability to affect or impact the future, we wouldn't have the surveillance state now. After George Orwell came up with 1984, we would not have needed Snowden.

So what I actually see science fiction being used for is the same thing that I see religion being used for you. The Bible, the Qur'an or whatever religious text you use, says so many different contradictory things that whatever your belief, you can find something in there to justify it. And science fiction throws so many darts at so many walls that just through random chance some of them are bound to hit the bull's eye. And so you can tell “Aha! Science fiction predicted this! Science fiction inspired that". But what you're doing is really picking and choosing from this enormous buffet called science fiction to justify something you have already decided to do, because the Koch brothers just gave you 5 million dollars for your campaign. You've got to come up with some of the selling.

Which is not to say that I don't think science fiction has the potential to do that. I think it has the potential to be enlightening and I think it does explore. This is why I write the damn stuff. It explores really cool ideas. It is the only literature that was designed from the ground up to explore the impact of scientific and technological change on the human condition. No other literature is big enough to do that. But even though it serves that role and even though I think it is vital in that role, nobody pays attention to it, nobody outside goes to science fiction to say "How are we going to shape our society?". It's a resource but it's a completely unexploited one, it's really only conscripted to do things that have already been decided and you're looking for excuses to justify it or to sell it to, you know, the under-twenty crowd.

M: Yeah that's maybe a bit pessimistic.

R: Yeah, I totally agree. I see the potential of science fiction in maybe sneakily rewriting something... when you read it and think about it, when you read Dhalgren and you don’t really understand what is happening, but something’s changing in your assumptions.

PW: It does rewire you. Basically science fiction acts like Snow Crash, except it doesn't give you a whiteout in your brain, but it actually does rewire certain neural pathways. But then again, so does every ad you see in a bus stop. The whole point of advertising is to use visual stimuli to rewire your synapses and make you more likely to buy something.

R: So let's talk a bit about neuro-pathways and synapses. You're going to be mentioning in your talk tomorrow the “Neuralink” company or maybe not the company itself but the concept behind it.

PW: Neuralink is in the news these days, so they are a perfect exemplar -- they're the ones that everybody's talking about.

R: It's an awesome technology, the idea of it, but there are a lot of implications in terms of society, for example. It's a neutral technology, but it could be used in very oppressive ways, just as many other new discoveries and initiatives like colonizing Mars, for example (who will colonize it, to what purposes, etc). Do you think we need to start rapidly democratizing our mechanisms to exert some control over technologies and how they're used and distributed?

PW: How do you mean democratize? I mean, democracy gave us Donald Trump.

R: Well, maybe it’s the concept of democracy itself that is problematic.

PW: Yeah well, the thing is when you when you talk about democracy... You know, Heinlein is an enormously problematic author in many ways, but there's that great line from him that democracy is predicated on the assumption that a million idiots can make a more intelligent decision than one smart educated human being.

M: What about making it accessible to a wider audience?

R: Making accessible the actual work of researching, taking decisions? For example, David Brin has this idea that democracy in itself doesn’t mean anything, unless you have these arenas of thought to do serious decision making in a more or less neutral, objective way. Like, for instance, in science, peer reviewing, that sort of thing, which is not really accessible to the average person. Do you think we need to reinforce such mechanisms, to allow people to have greater access to them?

PW: The whole point of sort of a neutral fact-based environment is that when you are presented with facts you will be swayed by facts. More and more we're discovering that there's this famous backside effect: You can actually show somebody absolutely incontrovertible evidence that their opinions on something are wrong. And their response to that more often than not will be to dig in their heels and believe that they're right even more than they did before. It's not necessarily the case when you're talking about something neutral like when the next bus is coming or whether a particular type of shoes is more fashionable. But if you're talking about political affiliation basically you are talking about anything that impacts your membership in a tribe, your social standing. Yet the tribe you believe in, the tribe that you are a member of, the one to be accepted by denies climate change. Then no matter how much evidence you are presented with, you will continue to reject climate change because your main goal is not to dispassionately parse information about the world. Your main goal is to achieve social acceptance in a tribe that will protect you from other tribes.

And in fact they found some really interesting results in that the people who deny climate change are not necessarily ignorant and uneducated doofi. They have found that some of the strongest opponents of things like that are extremely well educated and have tools at their disposal, which allow them to pick holes and to twist things and to use... There's a famous book, I don't know if it was ever translated in Bulgarian. It’s called How to Lie with Statistics and it basically just shows how if your results aren't significant, you can use this particular test to make it look significant. The more educated have the greater access to those kind of truth-twisting tools. So in many ways education is not the answer, because, I think as Einstein said, you cannot reason, you cannot argue somebody away from a position that they did not arrive at through reason.

So yeah, if you actually take the sort of naive economists’ view that everybody is rational, then yes, putting people into a situation where facts rule is a great way to do things. Alternatively, what you do is you find people who are completely disinterested -- whether or not climate change exists, that doesn't impact their social standing. I don’t know, maybe take people away and stick them at colonies where they never see another human being and they don't have to worry about social standing. There might be some social mechanism whereby you can divorce the analysis from the society. I've got nothing against the idea in principle, I think its implementation is going to be a real bitch.

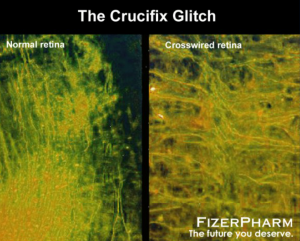

M: We're getting short on time, so let's move onto another area, maybe real briefly -- the art of writing. What stands out from Blindsight is your very meticulous and thorough approach to world building and the work that you've put into it. For example, this piece you did on vampires at the end that turns out to be hugely popular among the fans. How do you take something from a myth and put it very scientifically and rigorously in an SF context? Myth confronts vampires not only with crosses, but also garlic, holy water and light, silver. Did you try any of these other concepts and tried to fit them into the concept? Why did you pick the crosses in particular? What was the word building process?

PW: I don't know if you ever saw my powerpoint presentation on vampires? There's a slide at the end of it that shows various aspects of the vampire myth and the probable explanations for them. They presumably try all kinds of things from the garlic family to see if it will screw up with vampires and it didn't. Not being able to enter a house without being invited -- that's more likely. You can’t enter a house without closing your eyes, because the house itself will have so many right angles. If you enter the house with your eyes open, you will spazz out. The only way you can enter a house is to close your eyes in which case you gamble that you better be welcome in that house, because you're putting yourself at a significant disadvantage if you can't see.

But the whole vampire thing came from a completely different track. I was at a science fiction convention in Edmonton and some idiot put me on a vampire panel. This is long before I wrote Blindsight. And I didn't know anything about vampires, I wasn't even watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer at that point (M: You just lost the fans). I didn't know anything about this stuff but somebody put me on this panel and I had nothing to contribute. I still to this day don't know who struck me on that panel, but obviously I pissed somebody off.

But I thought I should contribute something and the one thing I did know something about was biology. And the vampire myth is really stupid when you think about it -- the various aspects of the vampire biology are pretty absurd. So I thought "OK, I need to use my biology kung-fu to try to rationalize". I had been reading some books about neuroscience and the biology of vision, with these Mexican Hat arrays and the way the visual receptors fire only responses to specific arbitrary stimuli… And so I came up with this idea for the crucifix glitch right there on the spot. "This is is why vampires can’t withstand crosses! It’s like a grand mal seizure because you've got two intersecting sets of visual receptors firing off in a feedback loop at the same time and that's why there are no vampires anymore because..." I hadn't said anything for the first fifteen minutes of this stupid panel and then I blurt out: “This is really great, aargh!”

But I thought I should contribute something and the one thing I did know something about was biology. And the vampire myth is really stupid when you think about it -- the various aspects of the vampire biology are pretty absurd. So I thought "OK, I need to use my biology kung-fu to try to rationalize". I had been reading some books about neuroscience and the biology of vision, with these Mexican Hat arrays and the way the visual receptors fire only responses to specific arbitrary stimuli… And so I came up with this idea for the crucifix glitch right there on the spot. "This is is why vampires can’t withstand crosses! It’s like a grand mal seizure because you've got two intersecting sets of visual receptors firing off in a feedback loop at the same time and that's why there are no vampires anymore because..." I hadn't said anything for the first fifteen minutes of this stupid panel and then I blurt out: “This is really great, aargh!”

And so I go in for a couple of minutes about the visual neurology of the vampire crucifix. There’s like crickets for a few seconds. And then the person next to me says “Yeah, so about that episode of Angel where Buffy does that…” (everybody is laughing) The positive thing about that was nobody everybody invited me to a vampire a panel of any kind again. But all of a sudden I had these vampire ideas. I was going to do like a coffee table book on the biology of vampires or something, I didn't know what I was going to do with it, I just thought it was kind of cool. But then I was writing Blindsight and there was this kind of a vampire-shaped hole. All the characters in Blindsight represented different facets of consciousness and there was this gap that needed to be filled. It sort of once again came to me in a dream that a vampire would fit perfectly. That's how that happened.

R: I was just going to say that I think that maybe this is one of the greatest things about science fiction, it just allows you to do these thought-experiments. And then something amazing sometimes happens.

PW: Yeah, well I mean the whole point of science fiction is not to say this is the way it’s going to be. More like what if this is the way things were and what are the consequences. That's awesome.

M: Science fiction conventions is where you came up with this. Do you go to them often, do they work for you? What makes for a good science fiction convention and the context of this question is that we are going to try to pull off one here in Bulgaria and we are looking for inspiration.

PW: I think you've got a leg up, I think if I had to name the one variable that seems to make a science fiction convention really enjoyable for me is it doesn't happen in North America.

M: WorldCon this year is in Finland.

PW: I know and as far as I know I'm not going and, man, I would really love to. I mean there's one guy who's still trying to get me to sit in on a video conference panel with David Brin, but David Brin hates my guts. I referred this guy to a blog post where David Brin called me a liar and a sociopath and various things. So I don't think that's going to happen, but I was at Fincon back in 2013 and loved it, it was the best organized con I have ever been to. But I've also been to a different con with forty four thousand people! Four thousand people at a con! In Toronto we're lucky to get like over a thousand at cons. There's just something about the energy and the depth of the panels at all the European cons I've been at that has excited me and engaged my interest, even though I never speak the language. Now this could be, there could be all sorts of confounds in that. I'm no longer allowed into the US anyway, so I can't go to US cons. I've sort of been to the local Canadian cons and find them now just frankly boring.

M: You interact with fans often. One of our staff writers actually mentioned that she donated to you and you kind of researched her and wrote back to her and she was very impressed with it.

PW: I try to do that because nobody has to give me money, my stuff is up there for anybody to take if they want. It's almost anti-Darwinian to give away hard-earned resources for something you can have for free. So when somebody is kind enough to do that I don't want to just send them an auto response. I want to reach out to them.

M: When you do that research, do you come across interesting stories now and then?

PW: Sometimes yes. Actually my next novella that's going to come out is largely helped by a guy who gave me some money. I researched him and found that half the high energy laser patents in the patent office were by this guy. So I picked his brain on creating black holes using lasers. One of the coolest things about being a science fiction writer is I now have this huge range of people with expertise everywhere: from military tactics to neurology, to art. And they're all willing to help me out. Largely because they drop five or ten bucks into The Kibble Fund, I thank them and we started up a correspondence, because nobody ever expects to get a personal response. And I've actually had some people say "I'm really embarrassed you wrote me back. If I'd known you were going to write me back, I would have given you more money".

Also, when I was being criminally charged in the US, people started sending money. My entire legal defense was paid for by fan donations and some of these people gave me as much as a thousand bucks. People like Straczynski from Babylon 5 and Cory Doctorow gave me huge chunks of money. An investment banker who was a friend of mine gave me like ten grand. But other people gave me two bucks. And one person wanted to give me ten bucks but accidently hit the button twice and in the end gave me twenty bucks. Then they wrote back and said “Could I have that because I can't really afford to give twenty bucks?” I ended up giving them all twenty bucks back. You can't thank the rich person who gives you a thousand bucks and ignore the person who gives you two. Because the person who gives you two bucks obviously doesn't have very much money and they think it's important and it's all they can afford. It's a kind of like the biblical story of the widow who just puts a couple of coins in the offering plate because that's all she can afford but it's important to her. So I’ve basically come to the conclusion that no matter how big or little the donation, you’ve got to thank everyone.

Also, when I was being criminally charged in the US, people started sending money. My entire legal defense was paid for by fan donations and some of these people gave me as much as a thousand bucks. People like Straczynski from Babylon 5 and Cory Doctorow gave me huge chunks of money. An investment banker who was a friend of mine gave me like ten grand. But other people gave me two bucks. And one person wanted to give me ten bucks but accidently hit the button twice and in the end gave me twenty bucks. Then they wrote back and said “Could I have that because I can't really afford to give twenty bucks?” I ended up giving them all twenty bucks back. You can't thank the rich person who gives you a thousand bucks and ignore the person who gives you two. Because the person who gives you two bucks obviously doesn't have very much money and they think it's important and it's all they can afford. It's a kind of like the biblical story of the widow who just puts a couple of coins in the offering plate because that's all she can afford but it's important to her. So I’ve basically come to the conclusion that no matter how big or little the donation, you’ve got to thank everyone.

M: It’s very much community building in a way. I think we have to wrap it up, sadly. Hopefully we can get your contacts and talk to you again.

R: Maybe we can invite you again, to a festival.

PW: I would be happy to come back, I just basically jump at the chance to go, anywhere on this side of the Atlantic, with the possible exception of Russia. Russia scares me sometimes.

M: Haha! Well, thank you very much for your time and for this opportunity. Good luck tomorrow -- I am sure it will be great (and it was! - Random).